- Home

- Taylor Kitchings

Yard War Page 2

Yard War Read online

Page 2

I’ve always gone to Broadview Baptist Church, and I’m always going to Broadview Baptist Church. If it’s Sunday morning, it’s time for Sunday School; if it’s Sunday night, it’s time for Training Union; if it’s Wednesday night, it’s time for Prayer Meeting. Not to mention church softball, church basketball, Vacation Bible School, and a buttload of other “opportunities for worship and fellowship.” If the doors are open, we’re halfway down, right side of the middle section.

I had spent the night at Stokes’s house, and we stayed up real late, but I still had to jump up and run home and get ready for Sunday School. Stokes’s mom had taken us to see Goldfinger at the Capri, and it was all I could think about. When I told Mama, she said, “Doris Cargyle is a wonderful woman, but she and I obviously have very different ideas about what kinds of movies a twelve-year-old boy should watch.” It bothered me in a way I can’t really explain that she and Mrs. Cargyle had very different ideas. When I was little, the grown-ups agreed about everything.

It was hot in that Sunday School room, the kind of dry heat that stops up your nose and makes your back itch, and those rickety metal chairs were hard to sit in and people kept squeaking them. Plus, Mr. Dukes’s fingernails were so dirty, it was hard to listen to today’s lesson. What the heck was he doing before church, working on cars? He’s all bald-headed and creased in the face, too. I felt bad for thinking about it, though. Mr. Dukes could help his fingernails but not his face. I sat up straighter and tried to pay better attention so God wouldn’t make me bald and creased when I got old.

Mr. Dukes told us God watches everything we do and keeps track of how many times we sin. He said if we bump our heads or stump our toes, that’s God saying, “Cut out that sinnin’, or else.” I guess it must be true, but I don’t especially want God watching me go to the bathroom.

Today’s lesson was about Noah. Mr. Dukes told us about the flood and how after forty days, Noah sent out a dove to see if the water had gone down, and when the dove never came back, they were finally able to get off that ark, which had to smell pretty terrible if you think about it. And then God promised not to drown everybody again, and that’s why we have rainbows.

“Now, boys and girls, we need to talk about Noah’s sons, who fathered all the peoples of the earth,” said Mr. Dukes. “And the cursing of Ham.” Cursing ham felt about right to me. Especially cold ham with fat all in it.

“Let’s everybody put your Bible in your lap,” he said. “Ready? Genesis chapter nine, verse twenty-five!”

I’ve won the most Bible drills this fall and obviously turned to Genesis 9:25 faster than anybody else, and stood up before Donnie Rogers, even if he yelled “Got it!” Mr. Dukes didn’t know who was really first because he was too busy shushing Ramona McLowry. Ramona does have some long, thick blond hair. I’m not saying I like her or anything.

Mr. Dukes should have been shushing Tim and Tom Bethune and their buddies in the back. They’re the oldest members of the junior high Sunday School class and think they’re too cool to be in it and never shut up.

“ ‘Cursed be Canaan; a slave of slaves shall he be to his brothers,’ ” read Mr. Dukes. “ ‘He also said, Blessed by the Lord my God be Shem; and let Canaan be his slave. God enlarge Japheth, and let him dwell in the tents of Shem; and let Canaan be his slave.’ ”

I raised my hand. “I thought you said Ham got cursed. What’s that about Canaan?”

“Canaan was Ham’s son. It’s the same thing.”

“Well, why would Noah curse him?”

“Ham walked into Noah’s tent and saw Noah naked.”

“On purpose?”

“I believe it was an accident.”

“That doesn’t seem like much of a reason to curse somebody, if you ask me.”

Mr. Dukes looked at the back wall and acted like he hadn’t heard me. “Now, boys and girls, if y’all will look on over at chapter ten, you’ll see the names of all of Ham’s sons. Somebody tell me what it says there in verse six.”

“Cush, Egypt, Phut, and Canaan,” said singsongy Cathy Hathcock.

“That’s right. And who can tell me where Egypt is?”

“Africa,” I said.

“That’s right, son. Africa.” He looked from one side of the room to the other, like he wanted it to sink in real good that Egypt was in Africa. “Where the nigra slaves came from.”

“I thought you said Canaan got cursed,” I said.

Mr. Dukes squinted at me. He doesn’t like too many questions.

“We are learning what the Bible has to say about Africa.”

Then it was time for big church. Everybody scraped and squeaked their chairs and headed for the door. I was confused.

“Mr. Dukes, are you saying that since slaves came from Africa, slaves are okay with God?”

“I’m not saying anything, son. I’m letting my Bible do the talking.”

Sometimes Dr. Mercer’s sermons are about the same Bible verses we read in Sunday School, so I was hoping to hear more about Noah and Ham and Africa. Maybe Dr. Mercer could clear some of that up for me. But he started on something else. When he got to the part he always gets to about how we are all unworthy sinners who need saving from everlasting damnation, I knew I wasn’t going to hear any more about Africa today. I don’t know why I thought I might. Dr. Mercer never talks about colored people.

I started doodling on the bulletin and drew a big round face with no hair and creases on it and eyebrows slanting up toward each other and a wriggly mouth that curved up just a little on both ends, like a smile you would make if you accidentally let out a big one in the sanctuary. Farish saw what I drew and laughed till she had to pretend she was having a coughing fit. I wrote, “Hi, boys and girls, I’m Mr. Fart!” under the face, and she had to cough some more.

Daddy looked over and saw what I drew, and he started coughing, too. Mama snatched it out of my lap.

—

On the way to meet Meemaw and Papaw for lunch, I told Mama about today’s Sunday School lesson and asked her if she’d ever heard Dr. Mercer talk about colored people. She said she never had. I asked her why, and she said she didn’t know. Daddy took his eyes off the road and raised his eyebrows at her like she did too know.

“So you do know?” I asked her.

“It’s complicated, pal,” Daddy said. “Let’s talk about it later.”

I nodded, but I still wondered about Dr. Mercer. He was the preacher, after all. My history teacher, Miss Hooper, talks about them. Miss Hooper is the prettiest teacher at the whole school, you can ask anybody. She has big eyes, greenish-bluish, like the water at Pensacola, and long blond hair piled up, and man, she is stacked. Her whole body is kind of perfect. She’s from Jackson but she has a boyfriend in law school way up in Maryland or somewhere. That might not be true. I’ve never seen him.

She told us about Medgar Evers, how he tried so hard to help colored people be able to vote and got shot in his driveway for doing it. And she told us how three Freedom Riders from up North got killed in Philadelphia last June for trying to help colored people vote. I thought Philadelphia was only in Pennsylvania, but it turns out we have a Philadelphia here.

Sadie Rae Jenkins raised her hand and said it was a shame the way everybody hates Mississippi, and she didn’t have any KKK in her neighborhood.

I was thinking, What do you know, Prissy-Pants Jenkins said something right for a change. I don’t want to live in a place everybody hates, and I don’t see why they should hate us, at least not all of us. I don’t have any KKK in my neighborhood either. If somebody from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, visited my neighborhood and my school and my church, he wouldn’t find a bunch of mean white people trying to hurt colored people. They might say things about colored people sometimes, but people here are nice.

But Miss Hooper told Sadie Rae it wasn’t just a few Klansmen giving Mississippi a bad name. If a colored person couldn’t vote without somebody getting killed, Mississippi was giving Mississippi a bad name. She said the harde

st thing for her or anybody to understand about our state is how people who are so warm and kind and full of “Southern hospitality,” and who would never outright hurt colored people, can be so full of prejudice against them.

“But it doesn’t matter how people feel about it, it’s the law,” Nancy Harper said. “Public places have to be shared by everybody. The South has to integrate, especially the schools.” She says it “schoo-ulls.” She moved down from Ohio last spring and acts like she owns the place. She also says “look-it” and “you guys” instead of “y’all.”

“No we do not,” Bobby Watson said, crossing his arms. A couple of guys applauded.

“Brown versus Board of Education, 1954. Look it up,” Nancy said.

“Well, this is 1964,” Bobby said.

“Nancy is right, Bobby,” Miss Hooper said.

“The Civil Rights Act, July 2, 1964,” Nancy said.

“Oh, shut up,” Bobby said. “Not you, Miss Hooper.”

Miss Hooper said the South has no choice but to integrate schools and try to get rid of its prejudice, and to do that it will have to get rid of its ignorance and guilt.

“Guilt about what?” Bobby asked.

“That’s a good question. I believe there is still a lot of guilt about slavery in this culture, and about Jim Crow, even though the laws have been in effect for almost one hundred years.”

She told us that Jim Crow laws were named after a white guy who painted his face black in the 1800s and called himself “Jim Crow.” He did musical shows mocking colored people and making them seem lazy and stupid, not even real people. So the “real” people named segregation laws after him. And segregation was just another kind of slavery.

She pointed to everybody in the class. “It’s up to you to think about what kind of state you want to live in. It’s up to each one of you to improve your state’s image.”

I don’t know what she expects us to do. We’re twelve.

Daddy says prejudice is one reason he’s thinking about moving us to Kansas City. His friend from medical school has offered him a job at a clinic up there. Mama says she cannot bear the thought of “uprooting” our family like that, and it would just kill her parents, especially her mother.

When we got to the country club, Mama looked at me. “Don’t bring up anything about Dr. Mercer and colored people at the dinner table.” Like I didn’t know that already.

We usually have Sunday dinner at noon with Meemaw and Papaw, either at their house or the country club. “Meemaw Table Rules” are the same wherever we eat. The food is great, especially at Meemaw’s house, where it’s fried chicken or roast beef or pork chops, garden tomatoes, baby butter beans, mashed potatoes, fried okra, squash casserole, English peas, homemade rolls, cornbread, peach cobbler, Meemaw’s world-famous chocolate milk shakes, all kinds of stuff. But the rules are a pain. On the way home from Sunday dinner me and Farish always start crackin’ up about something or other—we’re just that glad to get away from Meemaw Table Rules.

Meemaw and Papaw were waiting in the downstairs restaurant, the Golliwog. Church lasts forever, and by the time we get to the club, my stomach is making outer-space noises and shrunk to the size of a peanut. Everybody knows us, and they all smile and wave when we walk in and we have to stop and chat at a couple of tables before we can sit down. Then, right when we’re ready to order, one of Daddy’s patients will come over, and when she finally leaves, some people from the church will come over, and I have to keep smiling until they leave, and then, if we’re lucky, we can finally get some food.

Me and Farish always order the cheeseburger with sautéed onions and greasy log fries and ice cream pie. All the food is good. And all the people eating it are white. And all the people bringing it are colored, except the manager, Mr. Lonnie. Today, I started wondering why that is.

The waiters smile when they come to the table. Papaw always teases them and they always laugh. They seem to really like him. They seem to like everybody. But I was watching Shelby, the tall one with the white hair who’s been here ever since I can remember. Does he really like everybody? I wonder if he’s thinking, You better leave me a big tip, whitey-butt, if I have to smile this much.

Mama says Papaw’s bank that he started is the third-biggest in the state of Mississippi. I asked her if that meant he was the third-richest man in Mississippi, and she said him and Meemaw were “very comfortable.” I asked her why, in that case, it was so hard for him to hand over a nickel for a pack of Juicy Fruit. She said the Great Depression taught him the value of a nickel. So I don’t know what kind of tips he’s leaving Shelby.

I knew I couldn’t talk about colored people, but I wanted to talk about Goldfinger so bad, I was afraid to open my mouth for fear of it slippin’ out. That would be violating Meemaw Table Rule Number One: Do not talk about movies. Even if you just watched the best movie you ever saw in your life, you cannot mention it at the table because Meemaw thinks movies are a “stench in the nostrils of the Lord,” and doesn’t know why they are allowed to be shown to the public, what with all the violence and women running around half-naked—which I say is the reason to go see ’em.

Rule Number Two is Do not talk about playing cards. Even if it’s Go Fish. Playing cards leads to gambling and gambling is sinful. After we got back from Goldfinger, me and Stokes played Battle for three hours straight, which was a new record. Couldn’t mention it.

Rule Number Three is Do not talk about dancing. Dancing is bad. I hate going to school dances, so it’s no problem not to talk about it.

Rule Number Four is Pretty much do not talk about anything. Except school and church.

I couldn’t have gotten a word in edgewise anyway, with Papaw carrying on like he was, about the country “goin’ to hell in a handbasket” and rock ’n’ roll being music for “yay-hos.”

He asked me if I had any thoughts on the subject of rock ’n’ roll, and I said I was too busy eating to have any thoughts. Everybody laughed. But by the time they brought the ice cream pie, I couldn’t stand it anymore.

“Have y’all ever heard of James Bond, agent double-oh-seven?”

Mama glared at me, and I went back to my pie.

When everybody was finished, me and Papaw and Daddy left the “womenfolk”—that’s a Papaw word—and went out to the patio. Daddy said he’d see if there were a couple of guys in the locker room looking for a foursome. Papaw lit up an Old Gold and said he’d be right there.

“It’s turning into a real nice day,” I said.

“Yeah!” said Papaw. He likes to give everything a big “Yeah!” I told him, like I always do, that I didn’t know why he liked cigarettes, and he said, like he always does, “It’s a filthy habit, son. I only smoke a few.”

He propped one foot on the curb, rested his cigarette arm on it, tilted his Sunday hat against the sun, and looked down at the golf course like he owned it—which he kind of does, I guess, since he was one of the people who started this country club.

Then I said, “Papaw, can you imagine anybody naming their kid Ham? I mean, why not Pot Roast, right?”

“Ham?” He just looked at me.

My heart was going to town all of a sudden. I had to just come out and ask.

“Papaw, do you think the Bible says white people are supposed to be the boss of colored people?”

“No, son, I don’t. I know there’s some that do believe that. But I don’t.”

“Have you ever thought Shelby and all them might get tired of waitin’ on white people’s tables all the time? I bet sometimes they wish they could sit down and eat.”

He laughed.

“It’s paid work.” He said it “woik.” He says “woik” for “work,” and “Hawaya” for “Hawaii” and “Colyarada” for “Colorado.” He and Meemaw are both from the Delta, where all the cotton gets planted. I never met anybody from the Delta who said his rs.

“We pay the Negroes good, and most of ’em do a good job. Everybody’s gettin’ along fine.” He patted me on the s

houlder. “Shelby gets plenty to eat, don’t worry.”

“You think they’re happy?”

“Do they seem unhappy to you?”

“No. I’ve just been thinking about it.”

He patted me again.

“You know, your meemaw and I give a lot of money to the church to help the poor people, here and in foreign countries. The maid gets her bonus every Christmas and Meemaw gives her extra clothes for her boys and girls and such as that. It’s all our Christian duty to help the coloreds.” He sounded kind of formal all of a sudden.

“What if there was a colored person who wasn’t poor and wanted to join the country club? Would y’all let him?”

“Well, you know, Trip, people tend to want to socialize with their own kind. They have their schools and churches and clubs and so on, and we have ours, and it’s probably best to keep it all separate. That’s the way we can best help ’em. Anyway, I don’t ’spect there’s a Negro around here could afford it.”

“Well, what if he was real hungry and just wanted to sit down and eat in the Golliwog? Would that be all right?”

He looked at me like he could not understand why in the world I would ask such a question.

“I tell ya what, you bring me a morally upstanding Negro who’s hungry and wants to eat in the Golliwog, and I’ll buy him lunch, okay?”

He smiled and flicked the stub of his cigarette into the grass. I always worry he’ll catch it on fire, but he never does. “You think we got all that straight? I ’spect your daddy’s wondering where I am.”

When we got home, I looked up the word “golliwog” in the dictionary. It turns out a golliwog is a doll with a black face or a white person who paints his face black. And “wog” is a word making fun of colored people. They named the dining room downstairs after the waiters? Are they saying this is where you can eat in the less fancy room and pretend you’re a colored person, who always eats in a less fancy room? I thought about Dee, and calling it the Golliwog seemed nothing but mean.

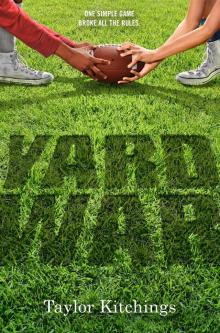

Yard War

Yard War